about VAaP

¿Desea ver esta página en español? Seleccione su idioma en la esquina superior derecha.

Quer ver esta página em português? Selecione seu idioma no canto superior direito.

Voulez-vous voir cette page en français ? Choisissez votre langue en haut à droite.

Vle wè paj sa a an kreyòl ayisyen? Chwazi lang ou anlè adwat.

آیا میخواهید این صفحه را به زبان اسپانیایی ببینید؟ زبان خود را در گوشهٔ بالای سمت راست انتخاب کنید.

Jump to:

What is VAAP?

Vermont Asylum Assistance Project (VAAP) is a legal services and technical assistance organization that exists to raise Vermont noncitizens’ awareness of and access to critical immigration legal help and support.

We achieve our mission through statewide direct service delivery, pro bono coordination, peer support, community education, and administrative and legislative advocacy.

Serving as a bridge between service providers and regulators across the state and region, VAAP educates the public on immigration issues and advocates for policies and practices that advance immigrants’ rights.

Our hyrbid-remote staff, service learners, and volunteers represent noncitizens statewide, periodically visiting community-based organizations as well as VAAP’s appointment-only Burlington co-working office, as our dynamic work requires. We are supported by a dynamic board of directors and collaborate closely with legal advocates and lay service providing partners.

What are vaap’s values?

We believe:

Immigration legal status is a means to the ends of noncitizens’ social inclusion, political participation, economic access, and community safety, rather than an end unto itself.

Just results for individuals facing legal harm are possible through authentic, vulnerable, and caring connections, and that the work of making systems more just starts with working on ourselves.

Impacted individuals, families, and communities are experts in their own experiences and needs.

A more equitable, inclusive, and just Vermont is possible for everyone regardless of legal status.

Quality, free legal services are one of many important tools Vermont must make available statewide to help immigrants pursue their individual and collective goals and make the best decisions for their lives.

We act according to our beliefs when we:

Embed legal advocacy within broader movements for equity and belonging, ensuring our services are rooted in a vision of collective liberation, not only legal status attainment.

Foster a culture of self-reflection, emotional integrity, and mutual care within our organization and across our partnerships, recognizing that personal transformation and accountability are essential to systemic change.

Co-create strategies, policies, and programming with community members most impacted by immigration systems, trusting and deferring to their lived expertise.

Center accessibility, equity, and cultural responsiveness in our work, affirming that Vermont’s future must include and uplift all communities, including all immigrant subpopulations statewide.

Expand Vermont’s access to harm-reducing, trauma-informed, and community-connected immigration legal support that respects clients’ agency and strengthens collective resilience.

What Is VAAP’s Vision?

We envision a future Vermont where all residents can access meaningful immigration legal assistance whenever and wherever it is needed, regardless of identity, experience, or status. We advance this mission through the creative, tireless work of a dedicated community of staff, interns, volunteers, directors, supporters, and partners.

Speaking of partnerships, our vision is to change the tide of immigration legal services infrastructure in Vermont for everyone so that all ships rise together. Review our 2025-2028 roadmap for immigration legal services sector development in Vermont.

how can we make vaap’s vision a reality?

Experience from other states shows that a complete, mature immigration legal services sector includes:

Coordinated no-, low-, and full-cost direct services across immigration subfields.

Pro bono support system to mobilize, mentor, and grow attorney volunteers.

Law school clinic pipeline tackling complex cases and projects on referral.

Federal and appellate litigation holding government accountable.

Embedded crim-imm advisors within public defense systems.

Statewide civil society coalition uniting immigration providers and allies.

Office of New Americans-equivalent driving public-private coordination (underway with VT 2025 Act 29).

Centralized resource hub (vaapvt.org) modeled on VTLawHelp.org.

Unified intake and referral system with statewide reporting.

who are vaap’s legal service partners?

VT’s immigration and related legal service provider partners, at a glance:

Vermont Asylum Assistance Project (VAAP): Removal defense, pro bono coord, tech assist, intake leadership.

Center for Justice Reform Clinic (CJRC): Law school clinic, removal defense, crim-imm consults.

Association of Africans Living in Vermont (AALV): CBO w/legal team focused on affirmative benefits apps.

U.S. Committee on Refugee and Immigrants (USCRI): CBO w/legal team focused on affirmative benefits apps.

Vermont Afghan Alliance (VAA): CBO w/legal team focused on affirmative benefits apps.

WISE Upper Valley: Upper Valley gender-based violence provider focused on immigrant survivor relief.

American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU VT): Judicial impact litigation, tech assist, education, advocacy.

Defender General’s Office (DGO) & Federal Defenders VT: Padilla advising, post-conviction relief in crim cases.

Vermont Legal Aid (VLA) & Legal Services VT (LSV): Civil legal aid on non-immigration but adjacent legal needs and self-help resources at VTLawHelp.org.

Principles for sustainable, community-rooted growth:

Support, don’t supplant: Build on trusted community infrastructure. For example, VAAP plans to develop and deploy VAAP-supported rural legal support workers who will rotate through community-based organizations (CBOs) on a regular basis to intake and serve clients where they are already at, rather than duplicate CBO infrastructure.

Evidence-based action: Implement data-driven practices and recommendations. For example, VAAP plans to actualize the recommendations from the Vermont Bar Foundation’s 2022-2024 longitudinal immigration legal needs study led by Vermont Poverty Law Fellow Maya Tsukazaki.

Proven models: Adapt successful frameworks from other states. For example, the national Immigrant Justice Corps is partnering with VAAP to pilot rural access to justice measures tin Vermont hat have helped close immigration justice gaps in other states.

Equitable, Vermont-sized solutions: Scale access to match community need, context, and values. For example, VAAP is working with partners statewide to diversify and redistribute immigration legal access more equitably across subpopulations, geographies, language access needs, legal status, and imminence of harm.

how can vaap & partners grow together?

Our work plan advances VT’s legal services sector by:

Supporting rather than supplanting existing and community-trusted infastructure, organizations, and institutions.

Implementing recommendations from Maya Tsukazaki’s $250K, Vermont Poverty Law Fellowship 2022-24 legal needs study courtesy of VT Bar Foudation.

Leveraging evidence-based infrastructure from other states proven to maximize social, political, and economic advancement.

Right-sizing immigration legal access infrastructure commensurate with VT values when communties need it most.

Prioritizing equitable, accessible support in every community.

what is the vaap FY25-FY28 roadmap for vt?

In service of our mission and vision, for FY26 we aim to achieve the following goals:

Expand and diversify defensive legal services—by case type and county—in ways that equitably meet the evolving needs of VT noncitizens.

Maintain and strengthen our organizational ecosystem—staff, volunteers, and partners—to ensure sustained delivery capacity.

Develop and drive adoption of our new intake workflow so VT knows how to request help and the sector knows how to meaningfully respond.

We will know we have succeeded in achieving these ends when we:

Provide a higher range, volume, and complexity of defensive legal services in more counties in FY26 compared with FY25.

Retain at least most of our current paid and volunteer staff and sustain partner engagement in technical assistance throughout FY26.

Increase calls for immigration legal help through the new intake workflow while decreasing calls via alternative channels.

Click here to review our organizational chart and budget infographics.

In order to expand and diversify services for objective 1, we will:

Mobilize and professionalize our growing team by redistributing operational responsibilities, standardizing practices, refining volunteer roles, and launching a Pro Bono Mentor Panel.

Establish and activate a Pro Bono Champions Council by engaging one Champion at each target firm, formalizing commitments, piloting offerings, and evaluating outcomes.

Augment rural legal service access by developing a statewide community based organization delivery model for mobile/rotating legal workers, mapping requirements, and piloting routes.

In order to maintain and strengthen ourselves for objective 2, we will:

Strengthen our operations and governance by empowering our inaugural Director of Operations and Intake Strategist to professionalize personnel policies, workflows, and practices and by routinizing Board committee support across governance, fundraising & outreach, and finance.

Ensure financial resilience and policy influence by implementing a sustainability plan that cultivates donors at all levels and embeds an annual foundation strategy into our CRM and by championing key legislative priorities, strategic committee work, and technical assistance trainings.

Incentivize and celebrate pro‑ and low‑bono partners by developing a recognition program to drive continued engagement and capacity growth, as well as a resource toolkit for firms and volunteers who commit pro‑ or low-bono hours or language support.

In order to develop and drive coordination for objective 3, we will:

Forge and deepen strategic partnerships and sector-wide impact by formalizing MOUs with key service partners and standarizing technical assistance protocols, pooled funding agreements, and coordinated service distribution.

Pilot a state-partnered immigration legal intake model by co-designing, testing, and staffing our universal intake line and evaluating pilot results to refine roles, workflows, and transition plans for FY27.

Drive VAAP’s future-of-services vision by leveraging the Intake Strategist role to capture intake data and stakeholder feedback, as well as the Act 29 ONA Study Committee to craft and advocate for a statewide blueprint for immigration legal services.

what is the VAAP work plan for fy26?

what was vaap’s impact in fy25?

In our first year of incorporation as a staffed 501(c)(3), despite systemic and existential threats, we made tremendous impact on immigration legal access in Vermont and established ourselves as an organization that is here to stay.

Click here to review our FY25 Impact infographic.

1. Immigration Legal Services Impact

50 full-scope cases opened, many protecting entire family units.

300+ asylum seekers served through clinics and walk-in events.

5 detained Vermonters returned home, and many more were screened or advised.

13 proceedings terminated and 35 immigrant juvenile cases opened.

Hundreds of applications filed, with dozens of work permits and benefits successfully issued.

2. People Power Impact

30+ volunteer attorneys contributed 3,000+ hours, supporting over 65 families.

VAAP grew from a solo Executive Director to 4 lawyers with support staff, with 2 more joining in late 2025.

40+ service learners contributed over 5,000 hours of support.

4 volunteer attorneys embedded, providing 3,000+ hours of direct representation to 30+ clients.

Dozens of volunteer interpreters helped save $20K+ in language access costs.

3. Policy Change Impact

5 pro-immigrant bills passed in Vermont (Acts 28, 29, 31, 66, and 69).

VAAP staff testified at 10+ hearings and presented on 3 panels in the State House.

Appointments to key committees, including the Federal Transition Task Force, VT Legal Hub Advisory Board, and the VT Judiciary’s Access to Justice Coalition.

Contributed to right-sizing state infrastructure, easing burdens on legal staff.

4. Media Momentum Impact

Created 2 podcasts and multiple KYR (Know Your Rights) videos in English, Spanish, French, and Creole.

Published 4 op-eds, appeared on 2 local TV shows, and achieved 30+ earned media hits from outlets including VTDigger, VT Public, NBC Boston, and the Washington Post.

Reached 62K site views and 25K unique visitors; materials were available in five languages.

Sent 25K newsletters with a 54% open rate (up 35%).

Engaged thousands at the grassroots level.

5. Education and Outreach Impact

Hosted a 400+ attendee Symposium focused on supporting pro se applicants.

Led dozens of KYR trainings across 13 of 14 VT counties.

Presented 12+ CLEs and panels, encouraging volunteerism in VT, NY, MA, and Quebec.

Weekly coordination with 10+ partners and extensive in-person and online training.

6. Revenue and Resilience Impact

Achieved $500K+ revenue growth, doubling FY25 income despite the loss of over $300K in federal funding.

Supported by 11 board members working across 3 committees.

Continued to serve as Vermont’s first host site for Immigrant Justice Corps (IJC) law fellows — 2 fellows hosted last year, 2 more in FY26.

Appointments to national and regional legal committees, enhancing VAAP’s visibility and technical leadership.

WHO are VAAP’s clients?

VAAP serves noncitizens in Vermont. For people seeking family- and employment-based pathways, we can share information and recommend trusted private practice attorneys. For humanitarian status seekers, like asylum seekers, we can screen for relief and hopefully offer direct immigration application assistance. Most people seeking help from VAAP are asylum seekers who have experienced forced migration, circumstances that pushed them away from their homelands and pulled them to Vermont as a place of refuge. While we might think about migrants collectively as “refugees,” the reality is that relatively few noncitizens arrive with “refugee” legal status. Instead, most immigrants are under- or undocumented and must submit applications to regularize immigration status and meet immediate and long-term goals.

What are VAAP clients’ goals?

Most immediately, VAAP clients’ most immediate goals are avoiding death, bodily harm, confinement in detention, and banishment through deportation. Once immediately safe, clients’ material goals include accessing a safe place to sleep, food and medicine for themselves and their families, and the opportunity to earn income to make the first two sustainable. Long term, most VAAP clients hope to live safely with their families free from the threat of deportation from the U.S. and free from the threat of harms faced in their countries of origin, let alone free to participate safely and equitably in public and political life.

What legal options further VAAP clients’ goals?

Quoting attorney Sarah Morando Lakhani, U.S. law offers three main pathways to regularized immigration status: family-based (based on “blood” relationships), employment-based (based on “sweat” relationships), and humanitarian-based (based on “tears” relationships). Programs like VAAP focus on humanitarian pathways and removal defense which are typically too time-intensive, politicized, and unstable for private bar coverage. Unfortunately, humanitarian pathways require applicants to excavate and display the depths of their worst experiences here or abroad without the outcome of justice being served. “Justice” isn’t an option for most but—depending on the bad things that have happened to them here or abroad—the law might offer tools to help clients meet at least some extraordinarily valid goals like immediate safety and meeting material needs.

When can VAAP clients become authorized to work?

Obtaining work authorization is usually VAAP clients’ most urgent goal. In the U.S., a work authorized social security number is the necessary precursor to working safely, opening a bank account, traveling safely between states, securing financing, and accessing public services and financial aid. Importantly, work authorization is not an independent immigration benefit one can apply for and is only available incident to some other pending “blood,” “sweat,” or “tears” pathway. Rules and processing times vary by pathways. Asylum seekers can apply for work authorization 180 days (or six months) after filing for asylum. Eligible individuals can apply for work authorization by submitting proof of eligibility and a current USCIS Form I-765.

What is asylum?

Since the mid-20th century, international and federal law have mandated that the U.S. must "withhold" removal of people who fear harm for things about themselves they cannot change or shouldn’t have to change (“protected grounds”) from which their government can’t or won’t protect them. In 1980, the Refugee Act added the option of discretionary asylum as an added benefit to withholding, offering more permanent status, family reunification, and potential U.S. citizenship. Asylum and withholding are just two of many “tears” based humanitarian immigration pathways and people are not limited to pursuing one at a time. Success depends not only on finding affordable counsel, which isn’t provided, but also on proving the “right” kind of harm to the “right” part of their marginalized identity at the “right” time and place. Even imminent death upon deportation is often insufficient.

Who is an asylum seeker?

When crossing international borders, forced migration is strictly regulated by law. When crossing inward across U.S. borders, forced migration is often wrongly labeled “illegal.” Federal law requires only that a person be present and afraid to invoke their right to a fair hearing on eligibility for asylum or withholding. There is no “wrong” way to seek asylum, and anyone present and afraid with an unexhausted claim is, by law, an asylum seeker. People cannot “be illegal” and the “a- - - -” word is harmful, even when being read out loud directly from the U.S. Code.

What does asylum seeking look like in Vermont?

In Vermont, the number of asylum seekers has risen sharply in recent years, but the state’s capacity for legal and advocacy support has not kept up. With one of the lowest attorney-to-population ratios in the country, Vermont struggles to provide asylum seekers with the legal representation they need, whether paid or pro bono. Without legal counsel, asylum seekers face enormous challenges in obtaining work authorization and meeting basic needs. They are also three to five times more likely to be denied asylum and deported, often to life-threatening situations.

In response, community-based organizations have stepped up to fill the gap. One example is the Community Asylum Seekers Project, which became VAAP’s first fiscal sponsor in 2016. VAAP builds on our partners’ on-the-ground expertise by combining it with strong legal connections. Together, we create a statewide resource center to train, mentor, and support attorneys and advocates while connecting them with asylum seekers who need help. Vermont is now home to a growing number of people seeking safety from countries like Haiti, the Northern Triangle, the African continent, and Afghanistan.

As an independent 501(c)(3), VAAP aims to expand this network of legal support. By leveraging our partners’ resources and expertise, we can provide hundreds more people with fair access to the legal system, the regulated economy, safe social inclusion, and the chance to live with dignity.

What are the risks, benefits of seeking asylum?

For most VAAP clients, preparing and filing asylum applications is materially emergent, but must be handled with caution and care. The sworn testimony those applications contain will follow an asylum-seeker throughout their immigration journey, lasting many years and possibly decades. Under the REAL ID Act, any inconsistent statements anywhere in the record of proceedings, however immaterial to the heart of the legal claim, can be used to find the asylum seeker “not credible” and deny their application. Denied applicants have limited appeal rights and, once exhausted, the government orders them “removed” and likely physically deports them. If the law prevents the government from granting someone asylum as a matter of discretion, the person may still be able to have their removal “withheld” but without the added benefits of permanent status, family reunification, or the ability to travel internationally.

How does someone apply for asylum?

If immigration officers detain a noncitizen within 100 miles of a U.S. international border, which includes most of VT, they can apply for asylum by stating (and repeating) that they are afraid of returning to their country of origin, want to be screened for asylum, and want to speak to an attorney.

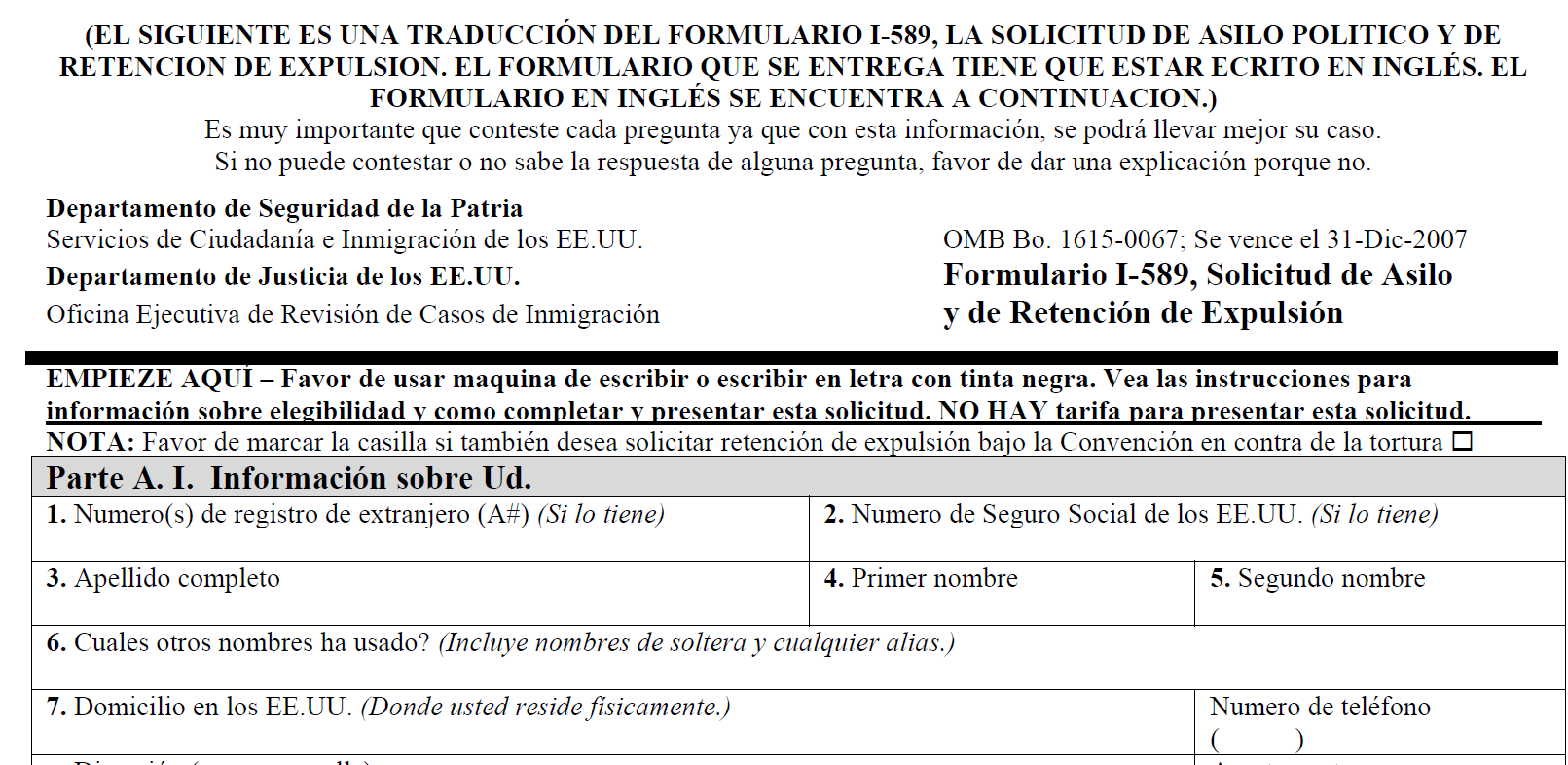

If a noncitizen is in the U.S. and not in removal proceedings before the Immigration Court, they can apply for asylum by filing a current USCIS Form I-589 with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

If a noncitizen is in the U.S. and in Immigration Court removal proceedings, they can apply for asylum by filing a current USCIS Form I-589 with the Immigration Court.

what makes a winning claim for asylum?

Without access to legal counsel, an asylum seeker is exponentially less likely to be granted asylum and instead be deported, often into life-threatening situations. Even with representation, the Executive Office for Immigration Review reports an asylum grant rate of only 41% as of 2024, a figure likely to worsen into the next administration. Under these unfavorable circumstances, VAAP aims to give Vermont noncitizens more just and open access to the U.S. immigration legal system so they can fully participate in our community and have a life of dignity—or at least meet their immediate safety and material needs along the way.

Access our virtual resource library here, request our legal help here, offer to volunteer here, learn about our non-legal partners here, attend our events here, follow our work here and subscribe to our newsletter here.

Does VAAP work on cases not involving asylum claims?

Short answer: Yes. VAAP assists not only with asylum but also with the full range of humanitarian immigration pathways—such as visas for survivors of crime or trafficking, protections for survivors of gender-based violence, Special Immigrant Juvenile Status for at-risk immigrant youth, and cancellation of removal for longtime residents in mixed-status families. Increasingly, VAAP and our partners are also pivoting into family- and employment-based immigration practice. Our staff and volunteer network brings experience across these areas, and through our leadership in the Vermont Bar Association Immigration Section we are cross-pollinating historically siloed practices so advocates can become more creative issue-spotters, including by expanding employer sponsorship opportunities.

Long answer: Yes. While asylum remains central to our work, VAAP is fully competent to assist with the full suite of humanitarian pathways to relief, including protections for survivors of trafficking or crime, Special Immigrant Juvenile Status for children who have been abused, abandoned, or neglected, family-based petitions, and other humanitarian applications. We also have a mandate from the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement—currently unfunded and pending our litigation in CLSEPA v. HHS in the Ninth Circuit—to ensure that no unaccompanied minor under 18 faces immigration proceedings alone.

Our staff and volunteer network bring significant experience in family and employment-based immigration matters in addition to humanitarian relief. Increasingly, we are weaving these traditionally siloed areas together to ensure that every client has the benefit of comprehensive issue-spotting across all potential options. For example, one formerly detained client we represented is now being sponsored by their Vermont employer for permanent residency, and we are exploring opportunities to expand employer sponsorships as a durable pathway to stability.

To advance this cross-pollination, VAAP also serves as co-chair of the Vermont Bar Association Immigration Section. In that role, we are working to break down the silos between family, employment, and humanitarian practice areas so that advocates statewide become more creative and effective in identifying relief strategies. We believe this holistic approach is essential for building resilience in Vermont’s immigrant communities.

Historically, frontline legal services organizations like VAAP did not take on the behemoth task of litigating constitutional or civil rights violations in the immigration system—issues like insufficient due process, violations of privacy or free speech, or cruel and unusual punishment. For individual services removal defenders, taking on the Department of Justice in federal court has always been a David-and-Goliath endeavor, especially now with dramatically expanded federal prosecutorial resources. That is where our pro bono partnerships come in. By pairing VAAP’s direct service attorneys—who know the immigration administrative system inside and out—with private bar litigators experienced in federal court, we can pursue judicial review of flagrant administrative failures. These collaborations will not only secure accountability for individual clients but also begin to shift the system toward greater fairness.

what options do Migrant workers and other longtime residents have?

Short answer: Even when someone has lived and worked in Vermont without status, there are often options. Many workers in farms, construction, healthcare, or hospitality may qualify for humanitarian relief (such as protection for victims of crime, trafficking, or family violence), for family- or employment-based sponsorship, or for other forms of relief that depend on their personal history. While not every undocumented worker will have an immediate pathway to status, careful screening often uncovers possibilities that can protect against deportation or lead to permanent residency.

Long answer: When we look at the migrant communities that sustain Vermont’s farms, construction sites, healthcare facilities, and hospitality industry, we know that many are living and working here with or without immigration status. Even when an under-documented worker’s primary reason for coming may have been economic, there are often legal avenues available once their full story is understood.

For some, humanitarian protections may apply based on harm they suffered or risk facing in their home country or in the U.S.—such as visas for survivors of crime (U visa), trafficking (T visa), or family violence (VAWA), or Special Immigrant Juvenile Status for children and youth who were abused, abandoned, or neglected. Others may be eligible for asylum-related protection if they also fear return, since economic migration and persecution are not mutually exclusive experiences.

In addition, many undocumented workers have family ties that can support petitions, or they may work for Vermont employers willing to pursue employment-based sponsorship as a pathway to permanent residency. We already have clients pursuing these routes, and we are expanding our capacity to support more employers in sponsoring workers indispensable to Vermont’s economy. Some of the most common pathways we screen for include:

U visas for survivors of crimes who assist law enforcement

T visas for survivors of trafficking

VAWA self-petitions for survivors of family violence

Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS) for children who were abused, abandoned, or neglected

Asylum or withholding of removal for those who fear persecution or torture if returned

Temporary Protected Status (TPS) or humanitarian parole in specific country conditions

Family-based petitions for those with U.S. citizen or permanent resident relatives

Employment-based sponsorships, including employer petitions for permanent residency

The most important first step is a comprehensive legal screening. People often assume they are “undocumented with no options,” but in practice, many qualify for relief they did not know about. Even if someone is not immediately eligible for permanent residency, interim protections can safeguard against deportation and provide work authorization while other applications are pending. Nowadays the most urgent barrier is preventing people from signing their fair hearing rights away under pressure from ICE before having had the chance to connect with counsel.

With Ice detention growing in 2025, how many detained immigrants have viable asylum claims?

Short answer: In 2025, the vast majority of people detained by ICE or the DOJ are bona fide asylum seekers with colorable claims. Over 70% of detainees have no criminal record (TRAC Quick Facts, 2025), and most are charged only with “irregular” immigration violations like presence without status or entry without inspection—grounds historically tied to low-income asylum seekers. Even when individuals do not ultimately win asylum, interim protection prevents deportation and gives them critical time to pursue other lawful avenues such as family petitions, humanitarian visas, or Special Immigrant Juvenile Status.

Long answer: This is an important and fair question. What we see in Vermont—and what national data confirm—is that the vast majority of people detained by ICE or the Department of Justice are bona fide asylum seekers with colorable, nonfrivolous claims. Legal representatives estimate the percentage closely tracks the share of people currently in ICE custody with no criminal record: over 70% of detainees as of August 2025 (TRAC Quick Facts). Most of this group are detained on removability charges for civil “irregular” immigration violations like presence without status or irregular entry—charges historically tied to lower-income asylum seekers.

Asylum seekers facing INA §§ 212(a)(6) and (7) removability charges almost always entered “irregularly” because of race and class barriers, and the method of entry has no prejudicial effect on asylum eligibility. Only a relatively small group—those with more resources and privilege in their home countries—can obtain passports and unrelated visas (tourist, student, temporary worker) to enter the U.S. by plane. Once here, they may pursue asylum “affirmatively” through USCIS, avoiding removability charges and the adversarial process where ICE counsel cross-examines the veracity of their traumatic stories. By contrast, the vast majority must undertake dangerous land or sea journeys. Some travel first to countries like Brazil or Nicaragua and then continue north on foot. Others cross multiple borders overland or attempt risky boat routes. These asylum seekers often lack literacy, formal education, and familiarity with government systems—or today’s increasingly digital immigration process. They typically apply for asylum “defensively,” in removal proceedings triggered by their civil immigration violations.

It was once extremely rare for asylum seekers charged only with “irregular immigration” violations to remain detained. Congress delegated detention authority to ICE and CBP to protect community safety, national security, and compliance with proceedings. Historically, only individuals with serious criminal convictions or extraordinary terrorism-related concerns were subject to mandatory detention. Today, however, ICE opportunistically detains anyone chargeable with any ground of removability, whether encountered in the 100-mile border zones (which encompass most of Vermont) or targeted outside immigration courts where asylum seekers attend previously scheduled hearings.

Even for the 30% of detainees charged with a criminal conviction-related ground of removability—sometimes for conduct as ordinary as working in cannabis fields, which constitutes a federal controlled substance violation, or pleading out to misdemeanor charges that would not even carry jail time—very few criminal charges strip a person of the right to seek protection from persecution. Some may limit eligibility for asylum (a pathway to permanent residency and citizenship), but individuals remain eligible for withholding of removal, which prevents deportation to danger and provides work authorization.

The takeaway is that the overwhelming majority of ICE detainees, whether facing “irregular entry,” criminal, or other removability charges, are bona fide asylum seekers with unqualified rights to be heard on their fear of return. Even if someone does not ultimately prevail in their asylum case, interim protection from deportation is life-saving: it creates the time and stability needed to pursue other lawful avenues—such as Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, family-based petitions, or humanitarian visas—that can lead to permanent status or at minimum protect against removal while pending.

That is what the law requires. But fewer and fewer asylum seekers are able to access and exercise those fair hearing rights. By law, any person in the U.S. who fears returning home has a right to be heard on that fear (INA §§ 208, 235, and 240). In practice, ICE and CBP control the initial pivot into that process—and increasingly use detention and coercion to block access. Just last week at NWSCF, for example, we met a detainee whose medication ICE officers withheld in an effort to force him to sign away his asylum rights and accept self-deportation. We have heard similar accounts across the 40–50 individuals our staff and volunteers consulted with this summer at NWSCF and CRCF. Many were detained despite clearly qualifying—or even already being approved—for humanitarian protection, including asylum, Special Immigrant Juvenile Status, or crime- and trafficking-related visas. The problem is not that detainees lack viable claims, but that ICE and CBP obstruct access to the rights Congress has guaranteed.

Most detained migrants we meet are not only eligible for asylum hearings—they often have strong underlying claims. What is new is the way ICE and CBP are using detention, coercion, and criminal charges to prevent people from ever asserting those rights, even though interim protection is itself critical to safeguarding life, family unity, and long-term pathways to lawful status.

How many detained asylum seekers have access to legal counsel?

Short answer: Detained asylum seekers have historically been much more likely to win relief when they have lawyers, but the vast majority in detention go unrepresented—an estimated 90–99% lack counsel at the “credible fear” stage (Human Rights First, 2022). Representation makes a huge difference: detained people with lawyers are nearly 11 times more likely to pursue asylum or other relief and about twice as likely to succeed if they apply (American Immigration Council, 2016). Today, government practices presume ineligibility without fair hearings, impose new fees of $100 to apply for asylum and $700 to appeal an adverse decision to the Board of Immigration Appeals, and limit immigration judges’ discretion to release people from detention, making it functionally impossible for many to fight their cases. The result is that many people with viable claims are being coerced into signing their own deportation orders out of fear, before ever getting a fair hearing.

Long answer: Historically, asylum seekers in detention who have counsel are far more likely to succeed. One nationwide study found that detained immigrants with representation were almost 11 times more likely to seek relief and nearly twice as likely to succeed compared to those without lawyers (American Immigration Council, 2016). But the vast majority of detained asylum seekers still go unrepresented: at the “credible fear” stage of asylum fair hearings administered by ICE and CBP, as many as 90–99% of asylum seekers do not have a lawyer (Human Rights First, 2022). Without representation, success rates plummet—unrepresented affirmative asylum applicants won only about 18% of cases, compared to much higher success rates for those with counsel (TRAC, 2023).

Even with lawyers, outcomes are increasingly stacked against asylum seekers. While asylum grant rates rose modestly under Biden—from 29% in 2020 to 37% in 2021—this remains a denial-heavy system, with pockets of higher approval rates in places like Boston and New York Immigration Courts, which preside over Vermont cases (TRAC, 2022). Many advocates now litigate with the expectation that they will lose at the trial level and need to appeal. Appeals, however, now carry a $700 filing fee to the BIA, on top of new fees for asylum and other relief applications. With more than two million cases pending in the immigration court system, the average wait for an initial resolution is 4.5 years and growing (National Immigration Forum, 2024). For detained individuals, that means the prospect of spending years in ICE custody while appeals grind forward.

This reality is terrifying and unsustainable. Detention itself is unhealthy and unsafe, particularly for asylum seekers and families fleeing trauma. People find themselves caught between the fear of returning to danger and the fear of indefinite detention in the present. Faced with these pressures, today many Vermont detainees are signing their own deportation orders or waiving their rights before they have even had the chance to reconnect with family or consult with counsel. On the ground, when we go into facilities, we are often the first to explain what asylum rights actually exist, and we routinely intervene to stop unlawful removals or transfers to remote, hostile jurisdictions.

The bottom line is that the government is not just tracking low “favorable outcome” statistics—it is actively suppressing them by denying hearings, raising fees, limiting judicial discretion, and coercing self-deportation. For this reason, we litigate every case with the expectation of appeal, knowing that interim protection can be lifesaving even if prevailing in the system is increasingly stacked against asylum seekers.

How does detention impact Asylum success?

Short answer: The underlying probability of success for detained asylum seekers is extremely low — not because their claims lack merit, but because ICE controls the first step of the process through “credible fear” screenings and often coerces people into waiving their rights. Nationally, fewer than one in five detained asylum seekers without counsel prevail, compared to roughly half with counsel (CRS 2024; American Immigration Council 2016). But in detention, that baseline probability is suppressed even further: ICE officers administer the screenings, routinely deny access to interpreters, and sometimes use illegal coercion tactics like withholding food or medication. The officer’s word carries the record, and detainees rarely have the chance to contest it.

Long answer: The question of “underlying probability of success” for detained migrants is complicated because the system itself is designed to reduce that probability. By law, asylum seekers detained at the border or in interior enforcement are supposed to undergo a “credible fear” or “reasonable fear” interview — a threshold screening that should be relatively low-bar. But unlike other legal proceedings, this step is administered directly by enforcement agencies like ICE and CBP, not neutral adjudicators.

That means the underlying probability is skewed from the start. Reports from Vermont and nationally show that ICE officers have used coercive tactics — including withholding food and medication, denying access to interpretation, and misrepresenting legal rights — to pressure detainees into waiving their claims or signing self-deportation orders. Because the officer’s word typically controls the official record, detainees’ objections rarely make it into the file.

Data help illustrate how the system suppresses outcomes. According to the Congressional Research Service (2024), only 19% of unrepresented asylum seekers achieved relief, compared with 47% of those with representation. A 2016 American Immigration Council study found that detained immigrants with lawyers were four times more likely to win release on bond, yet only 14% of detained immigrants had counsel at the time, compared with 66% of nondetained immigrants. Today, Vera Institute of Justice reports that 63% of detained immigrants still lack legal representation. In practice, this means the “absolute” probability of success for a detained person is vanishingly low without counsel, and heavily dependent on geography, detention conditions, and access to pro bono support.

The bottom line: the underlying probability of success for a detained asylum seeker is not a true reflection of the merits of their claim. It is a reflection of structural barriers — ICE’s control of the first procedural step, coercion and rights violations at detention facilities, lack of counsel, and systemic obstacles to appeals. The result is that people with strong asylum claims are being denied protection not because they don’t qualify, but because they never receive a fair chance to prove it.

How many in Vermont have had temporary protection revoked in 2025 and now risk detention?

Short answer: We don’t have exact numbers, since TPS and parole data aren’t reported at the state level (CRS), but we estimate that Vermont has a couple hundred residents with temporary protections like TPS or humanitarian parole, including Biden’s CHNV parole program. Many of these individuals have strong asylum claims but haven’t applied because there are not enough asylum lawyers in the state, and because people know how much less likely they are to prevail without counsel. VAAP is addressing the dearth of reliable state-based data by launching coordinated statewide intake next month and supporting the new ONA study committee under Act 29 (first meeting was August 29, 2025) to build the first reliable picture of TPS and parole holders in Vermont.

Long answer: We do not currently know exactly how many Vermonters have had Temporary Protected Status (TPS) revoked, because TPS is administered federally and DHS does not publish state-level data (CRS Overview; Immigration Forum Fact Sheet). What we do know is that Vermont has a small but significant immigrant population (AIC Vermont Map), and nationally TPS holders contribute enormously to the economy (AIC Economic Contributions). Based on our caseload and community knowledge, we estimate a couple hundred people in Vermont currently hold temporary protections—including TPS and humanitarian parole. That group includes many CHNV parolees (from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela) who always had a basis to seek asylum but often have not applied, both because of the shortage of asylum attorneys in Vermont and because they know how much less likely they are to prevail without counsel.

VAAP is actively working to close these data and service gaps. Beginning next month, our new intake strategist will coordinate a statewide intake process so we can identify TPS and parole holders and assess their needs. We are also supporting the Office of New Americans (ONA) study committee established under Act 29, which held its first meeting on August 29, 2025, with a promising start. That process will help Vermont build its first comprehensive picture of immigrant populations statewide, including those with temporary protections.

For people who lose TPS or parole, asylum is not the only option. Depending on their circumstances, they may qualify for:

Family-based petitions through U.S. citizen or permanent resident relatives

Employment-based sponsorships, especially as Vermont employers increasingly step up to sponsor essential workers

Humanitarian protections like U visas (for survivors of crime), T visas (for trafficking survivors), or VAWA relief (for survivors of family violence)

Special Immigrant Juvenile Status (SIJS) for young people who were abused, abandoned, or neglected

Withholding of removal or humanitarian parole as interim protections that prevent deportation and allow work authorization

The prospects for success depend on each person’s history, ties, and relief options — and now, the expediency with which they can access counsel to counter ICE coercion. Even if someone cannot qualify immediately for permanent residency, interim protections are lifesaving because they allow people to remain safely in the U.S., reunite with families, and pursue lawful status over time. The bottom line is that Vermont’s TPS and parole holders should not assume they are out of options. Lack of state-level data has made them less visible, but VAAP is working to change that. By coordinating intake and supporting the ONA study committee, we are building the infrastructure to track, support, and expand pathways for TPS holders, parolees, and others who deserve stability and protection.

How can I work with VAAP?

If you are a potential client looking for immigration legal help, visit our Get Legal Help page here. If you are reporting suspected or confirmed ICE actvity in Vermont, report it to our ICE Tracker page here. If you are an legal worker or language access provider interested in volunteering, visit our Volunteering page here. If you want to browse our self-help information, access our Virtual Library pages here. If you are a community partner and you’re interested in collaborating with us, join us at our next virtual case rounds linked on our Calendar page here. If you are just looking to subscribe or get in touch, access our Newsletters page here.